Do you remember the first time you donned SCUBA gear and took your first breath underwater? Do you remember that indescribable feeling of amazement and wonder?

Well, diving under the ice is just like that.

With good visibility and light, you can look up and watch the bubbles play across the ice above you. The cracks and creaks of the ice shelf give the water a music-like quality. It is just, indescribable.

But ice diving comes with a unique safety issue that shares much more in common with cave diving than it does no-overhead diving: you can’t just surface if there is an issue, and the potential of losing your only exit from the ice is both very real, and very possible.

Ice Diving Safety

Many divers are under the impression that simply looking up will allow them to find the hole they entered through, and they can just make their way out. That is not the case and should not be relied upon as a safety measure.

So what safety procedures are in place to protect divers under the ice?

In line with ERDI standards, and our own safety standards, we continually reinforce the concept that divers in any NePSD Ice Diver Class will never enter the water without a locking carabiner tether in the locked position. Safety divers wait on the surface, tether attached, and divers are tethered before entering the water.

This importance cannot be understated, as that tether can often be the only thing that will reliably get a lost diver back to the surface. Without that route back to the entry hole, a diver could conceivably drift or wander in any direction and never get back to the surface.

In Public Safety Diving, though, one safety is never enough.

What Happens if an Ice Diver Loses That Tether

So what happens if a diver’s tether becomes unclipped? What does a diver do if their only lifeline suddenly disappears and they don’t realize it before that lifeline slips away? What does topside do when the tether line goes slack and a diver stops responding? Where should they look first to ensure they get that diver back before the diver runs out of air?

All great questions, and we’re going to show you what to do.

So we’re clear, any operation that is a rescue effort for a live victim will be worked according to the conditions presented. In those situations, the primary goal is to save a life and for that to occur, speed and efficiency is key.

In this article, we will be addressing non-rescue operations (recovery of some sort, or training). These operations afford the greatest degree of safety for divers because we have all the time necessary to properly plan the operation and arrange the required support for a safe dive.

The Safety Equation: Ice Diver Planning

As we’ve mentioned, ice diving is far more reliant on tether limitations than other forms of PSD diving and the operation needs to be established carefully on that fact (this will become clearer in a moment). When discussing ice diving, never forget that the tether is absolutely show-stoppingly critical.

So, to make sure we’re clear, under no circumstances should divers enter ice conditions without a tether. Nothing is worth a diver’s life and we can’t rescue victims if we can’t locate the exit hole.

Now, when the dive location is chosen (or, in the event of a recovery, chosen for us) a hot zone needs to be established and proper ice safety procedures followed (a topic for another discussion). Test holes should be cut and the depth of the water sounded so the depth becomes a mostly-known variable.

Why is this important?

First, because we’re standing on the ice directly over the dive location. Sounding takes minutes, requires gear that is virtually free, and is exceptionally easy to do, so, why not? Second, we need to know the operational limits of the divers based on the dive location and plan the operation accordingly.

Determining Operational Limits of Ice Divers

To explain this better, let’s come at it from the safety standpoint.

In the event that a diver becomes lost and untethered (worst-case scenario that can easily turn life-threatening) the correct procedure is for the lost diver to slowly ascend to the ice sheet, taking care to keep a hand over their head and not crash into the ice. Once the diver arrives at the ice sheet, they should inflate their BC to keep them against the ice, ditch their weight belt, place both hands against the ice and “get big”, meaning make themselves as big as possible. If they are carrying an ice screw, they should screw this in and secure themselves to the screw.

This lost diver is now a 5-6’ tall obstruction against the ice surface. At this point, they wait and trust that help is coming. The lost diver should NOT attempt to locate the hole if they cannot see it immediately. Doing so may result in the lost diver traveling in the wrong direction and eliminating any chance of finding them. Remaining stationary is critical.

Once the emergency situation becomes clear, all unnecessary surface operations cease and the safety diver is deployed. Because of the very high danger factor with ice diving, recovering the lost diver becomes the only operational concern. The Dive Supervisor will determine the lost diver’s most likely direction and inform the safety diver.

The safety diver will submerge, but only far enough to get under the ice. At this point, the safety diver will either swim or ice-pick their way in the direction of the lost diver, ensuring they stay against the ice sheet. At a predetermined point, topside will signal the safety diver to stop and begin their sweep.

Million dollar question: what is this predetermined point?

Ice Diving Operational Planning – Working Depth

Let’s pause this procedure and get back to the dive planning so we can understand this distance.

After the operational area is established and the depth is determined, the Dive Supervisor should establish the maximum distance a working diver will be allowed to travel away from the hole. For all you math majors out there, this formula is a triangle and the depth plays a key role in the fixed travel length of the working diver.

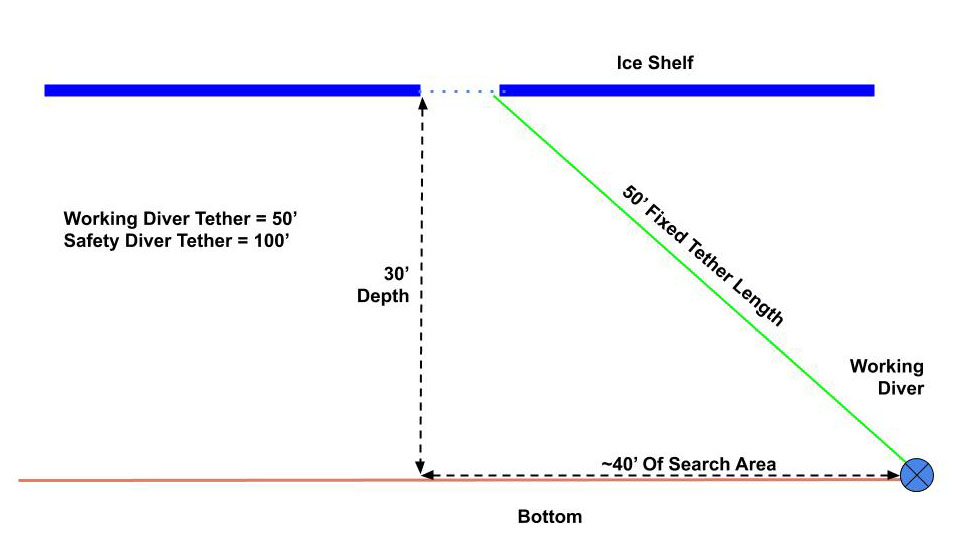

For example, if the working depth is 30’ then the Supervisor may fix the maximum tether distance at 50’ total from the surface. This will allow the working diver to reach the bottom (30’ of tether) and extend out in a search pattern (approximately 40’ in any direction). Or, at 15’ of working depth, a fixed tether length of 35’ feet will allow the working diver to extend 30’ in any direction.

This working distance is critical to understand because, in the event that the working diver becomes untethered and lost, they will surface to the ice sheet as discussed. The safety diver’s tether needs to be 2x the length of the working diver’s tether to ensure a quick location and rescue. If the working depth is not established, then the safety diver may be swimming much further than necessary to perform their sweep, fatiguing the safety diver and extending the period of time before the lost diver may be located.

For instance, if the working depth is only 30’ but the working diver is allowed to take out 100’ of tether, then the safety diver must extend out 200’ in order to ensure the lost diver is found.

So how does this sweep and rescue actually happen?

Locating and Rescuing a Lost Ice Diver

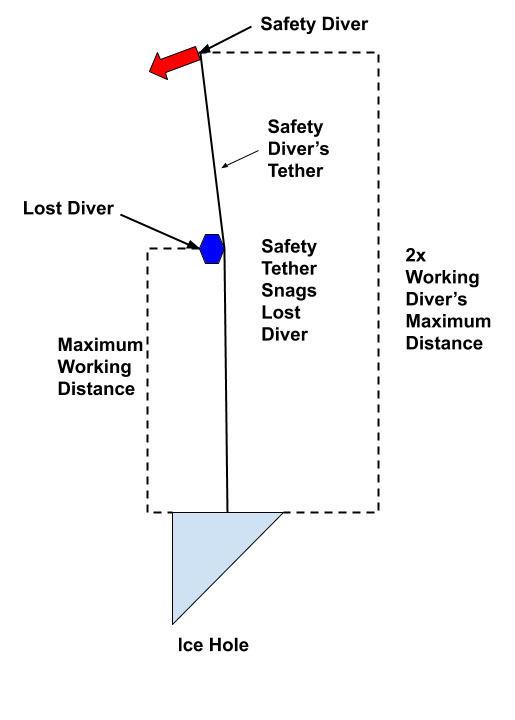

Getting back to our lost diver safety procedure, we now know how the predetermined length of tether line is calculated (2x maximum length of working diver’s tether), and we also know that the lost diver is hopefully “getting big” on the ice sheet waiting for rescue.

Once the safety diver reaches their predetermined distance, topside will signal them to stop and begin their sweep. That sweep amounts to nothing more complex than swimming left, or right, against their tether line, using it as the fixed center of a circle. Provided the tender keeps the safety diver’s tether tight, the safety diver will begin circling the entrance hole.

Assuming there is no current, the lost diver performed all procedures as trained, and the safety diver swims directly under the ice, the safety diver’s tether will eventually catch on the 5-6’ tall obstruction that is the lost diver. At that point, the lost diver should begin giving pull signals on the safety diver’s tether (preferably the team’s recognized signal for “IN” or “take up line”).

The safety diver, having felt the pull signals, will begin moving toward the tether until making contact with the lost diver. The safety diver will assess the lost diver and both divers will return to the entrance together.

Ice Diving is Amazing

Ice diving is the sort of activity that is unforgettable. There are so many new facets to diving under the ice that it amounts to the difference in experience between breath-hold diving and SCUBA diving.

With that wonder and awe comes a whole realm of critically important safety measures that must be in place in order to ensure all divers return to the surface to tell their tale. In the event that Murphy’s law kicks in, divers need to be prepared and ready to execute the safety procedures to get the lost diver back.

These safety procedures are just a single piece of the ice diving pie which we will be covering in future articles.